- Home

- Karin Smirnoff

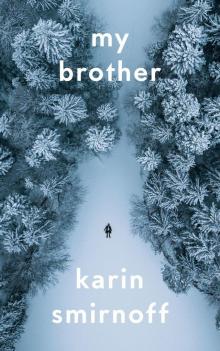

My Brother

My Brother Read online

my

brother

karin

smirnoff

Translated from the Swedish

by Anna Paterson

pushkin press

far awa from the warld

Far awa in the ill pairt

Lost in the warld

I play my melodium

for the pyne in my saul

The bellow is broke

Broke is my soul

Far doun in th’ill pairt

Lost in the warld

—Helmer Grundström

CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE

EPIGRAPH

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTYONE

TWENTYTWO

TWENTYTHREE

TWENTYFOUR

TWENTYFIVE

TWENTYSIX

TWENTYSEVEN

TWENTYEIGHT

TWENTYNINE

THIRTY

THIRTYONE

THIRTYTWO

THIRTYTHREE

THIRTYFOUR

THIRTYFIVE

THIRTYSIX

THIRTYSEVEN

THIRTYEIGHT

THIRTYNINE

FORTY

FORTYONE

FORTYTWO

FORTYTHREE

FORTYFOUR

FORTYFIVE

FORTYSIX

FORTYSEVEN

FORTYEIGHT

FORTYNINE

FIFTY

FIFTYONE

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

COPYRIGHT

ONE

I went to see my brother. Took the bus along the efour down the coast and jumped off at the stop for the village. Then I set out to walk.

It snowed heavily. The road was disappearing under the drifts. Snowflakes tumbled into the low tops of my boots and my ankles froze as they did in childhood.

I would have thumbed a lift but no cars came. My brother’s house was a couple of kilometres away up a slope.

I sang songs by everttaube to distract myself. Our parents loved everttaube and then they died.

The wind slashed my coat. The top button was missing and snow was melting against my neck. I should’ve got there by now. The snow made the landscape anonymous. Had I even passed eskilbrännström’s yet. I speeded up. For as long as the ship stays afloat. Then Who said just you would be born.

A bundle forced itself forward through the snow fog. A huddled human shape straining against the wind. At first I couldn’t see if it was a man or a woman.

The wind swerved. The snowflakes were handsized. For a few seconds the figure wasn’t there but then the wind blew its hardest and in the eye of the storm I saw who it was.

It was no one I knew.

Some weather he said when he had come close and I nodded. He wanted to know where I was off to and I said kippofarm.

Then you must’ve taken the wrong turning at the crossroads he said through his scarf. You should’ve turned right. I’ll come with you he said.

I could only make out his nose and eyes between the scarf and the woolly cap. Tried to catch his eye but he kept looking ahead.

We turned even though the compass inside me still pointed the opposite way.

He offered me his gloves. It was a long time since I’d shared somebody’s gloves. I couldn’t get my head round having gone the wrong way. We turned and walked back. Facing the wind and bending over like children lost on the high fells.

He lived nearby and his name was john.

I’m jana I said. I’m going to visit my brother.

And your brother’s name is bror he said. I know who you are.

Where were you going I screamed to be heard above the wind. It was gaining strength.

Nowhere he screamed back. I just like the wild weather.

He pointed towards a track where faint footsteps were still showing in the snow. I live along there, not far. Let’s go to my house and warm up. Then you can start out again when the blizzard has died down.

I hesitated because I didn’t recognise him but I ought to have. Besides, I knew that the track led to eskilbrännström’s house.

Do you live in the deserted house I asked and he nodded.

I didn’t know one could live there. With your family or do you live alone.

It’s the kind of place where one can only live alone he said.

The wind was still whipping snow against my neck. My face had lost all sensation long ago. I followed him.

He kindled the fire in the stove and found a pink woollen blanket to spread over me where I sat on the kitchen sofa in my longjohns and top while my clothes were drying over a chair.

It’s from the ume valley asylum he said. When the loonies were moved out all the stuff was sold at auction.

There was something familiar about the room and I thought that maybe I had been there before. The kitchen was worn in a quiet, gentle way. Apart from the sofa there was an ancient folding table a few handmade västerbotten chairs a tall dresser and a ticking clock though it showed the wrong time.

So it seemed he lived there. Probably slept in the tall old pullout bed that I was sitting on with my legs dangling because my feet didn’t reach the floor.

Do you live in the kitchen I asked as I cupped my hands around the hot mug he handed me.

Yes mostly he replied. In the winter anyway. In the summer I sleep in the attic or in the bestroom.

That bestroom now I wondered and held on to a distant memory. Does it have a painted ceiling. He nodded slurping his coffee from a saucer with a lump of sugar between his teeth like old people do.

I saw the bestroom in my mind as it had been. A pair of yellow rubber boots on a black chest. A chest that wouldn’t open. And how I finally had set to work with a flattened iron bar I had found plunged into the ground as a border marker. I shoved the bar in between the lid and body of the chest and heaved until the lock snapped.

Twentyfive years later I couldn’t remember what was in that chest. Perhaps nothing more than stale air.

He asked do you know who my brother adam was.

I didn’t know.

We were playing in the hayloft he said. Vaulting off roofbeams and landing in the hay. Adam was the elder by a few years and always dared more than I did. It didn’t help however much I tried to push back at my fear.

Earlier that day he had stolen some cigarettes and asked if I wanted to try one. I didn’t want to come across like a baby so I reached out for one of his nofilter glens and stuck it in the corner of my mouth while my brother lit a match. We didn’t realise that I might choke on the smoke have a fit of coughing and drop my nofilterfag into the hay. Finding a lit cigarette in a haystack is in principle as hard as finding a needle.

The newmown hay might well have smothered the flame if we had left it alone but the more we kept rooting around the more oxygen got in and suddenly fires flared up around us.

I hurled myself down to the floor of the byre and ran out into the sunshine and the air with thick smoke trailing behind me. I ran across the yard and up towards the farmhouse to get help but turned back when I discovered adam wasn’t behind me.

I shouted his name. Through a narrow gap between the fire and the smoke I saw his arm hanging down over the edge of the hayloft.

The man fell silent and pulled himself together. Busied himself at the sink. Caught coffee grains on a kitchen cl

oth and tugged at his big black mane of wavy hair to get it out of the way. Looked at me and explained.

The most likely thing is that the smoke got to him. I moved the ladder and held my breath and climbed up to him as quickly as I could. Managed to grab hold of his arm and tried to haul him down but he was heavy and I wasn’t strong enough.

That’s how it happened. I wasn’t strong enough to rescue my brother. Wasn’t even aware that my hair was on fire. Only how smooth the skin was on adam’s already dead arm.

It was his boots you saw on the chest if you wondered.

Such a sad tale. Still he could have been lying.

I felt drowsy from the warmth from the stove and the hot coffee. I should’ve got dressed and carried on walking up the hill to my brother but my body felt listless and resisted going back out into the blizzard. I pulled my legs up and tried to work out what that smell was. It wasn’t nasty. I imagined some foreign places might smell like it. A foostie smell my mother would have said and perhaps it was just old dirt I was sniffing for like a dog on the trail. But however much I sniffed I couldn’t identify it.

You sleep here if you like he said. I can bed down on the floor or sleep on a chair. It was a pullout bed. I usually find it distasteful to be physically close to people I don’t know but offered to share it with him. It would be a tight fit.

He blew out the lamp. It was only then it struck me that the house had no electricity. A rare kind of silence filled the shadowy kitchen as the wind snow and cold fought on the other side of the singleglazed windows.

It wasn’t easy to sleep. Hours passed while we listened to each other’s breathing. I was nearest the room and one of my legs was resting on the hard edge of the bed. He was pressed against the back of the sofa. I sensed his body against mine even though we barely touched. And when he breathed out I breathed in his breaths as if we were stuck underwater sharing an oxygen cylinder.

My leg slid back down into the bed. His arm couldn’t hold out any longer and fell back into an easier place. When my hand slipped into his relaxed fist my mind found peace.

It was light when I woke and the room’s mood had changed from last night. The windows were framed by sunbleached curtains. Wear and tear had left small rips in the weave. On the window sills, crowds of potted geraniums were almost about to come out of their winterdoze.

John was already up and about. He had put new logs on the fire and added a couple of heaped spoonfuls to the coffee dregs from last night.

I watched him from my horizontal position. An orange lumberjack sweater was doing things at the worktop by the sink. When the sweater turned towards me I saw his face in daylight for the first time and couldn’t resist the impulse to look away.

Don’t worry he said I’m used to it.

He laid the table with coffee cups soft flatbread butter and västerbotten cheese. Looked at me smiling a little and hoped I had slept well. Settled down with his saucer and sugarlump.

What happened afterwards I asked. I mean after your brother died.

This time my gaze lingered to observe the burnt skin that stretched across one half of his face and covered it with ridges like furrows on a sandbank when the water has drained away.

After adam’s death everything changed. We used to be no different from other smallholders scraping a poor living from work on the land. Dad would take forestry jobs in the winter and go fishing in the summer. When dad was away adam was in charge. Not mum. Her usual place was a stool next to the workbench. She ate what was left on our plates. It wasn’t that she saw herself as a menial. She did what seemed right to her.

For a while he sat in silence with his eyes fixed on the memory.

Dad blamed me for adam’s death. Insisted I could have saved my brother. Because I had a harelip and was hard of hearing I was sent away to a school in örebro where they were supposed to be able to cure both cleft lips and deafness.

How old were you I asked for chronology’s sake.

Ten, almost eleven.

I dressed. Pulled my trousers over the longjohns. My socks and boots had dried. It was still snowing but only lightly. The sun was fighting to get out from behind the massed clouds. It might be a nice day.

A soft light fell on his face. I wanted to touch the burnt skin so that later I could shape the clay to look like it but thought the gesture might be misunderstood.

May I look in the bestroom before I go.

Feel free.

The room looked just as I remembered it. The ceiling was decorated in faded rustic patterns and the timber walls were splatter painted.

Even the chest was still there but not the boots.

The biggest difference was the set of large oil paintings. The canvases had simply been stapled onto the walls. Paintings like stage sets. Fire smoke faces grass sea body parts rubber boots and hands all so skilfully painted the effect was photographic.

Are these yours I asked and he nodded. I paint now and then.

Have you shown them to anyone but no he hadn’t I was the first to see them.

You can paint I told him stunned by what I saw. It affected me so much I had to move on. As I backed out of the room the canvases formed the background to john in the foreground with his damaged face and large head of black hair.

I didn’t see only the paintings I saw myself my brother my parents. And there mum came running. Screamed you must do something. Save him. Excited cattle were bellowing.

The horse was neighing kill kill.

John raised his hand meaning bye see you. I did the same. And when I had closed the door behind me I ran until there was no more oxygen to keep me running.

TWO

We were drinking whisky in bror’s kitchen. Or, not really. Bror drank whisky and I drank tea. He had lit a fire on the hearth. I did my best not to see the dirt and disorder. We were born just a few minutes apart and are alike in many ways. Especially in how we look. We are thin and gingery, with straggly unpigmented hair. We are so bleakly unremarkable that nobody used to remember either of us as somebody. Only as the twins.

Has something happened that made you come here he asked.

Nothing special I said my mind on the paintings in the bestroom. I had nothing to do over easter that’s all.

It had grown late. We went for a walk with the elkhound. By now the sky was clear and starry once more. The mutt tugged us along at a brisk pace. The thermometer had dropped to minus twelve and the snow was creaking underfoot. Past göranbäckström’s there were no more streetlamps but the light of the snow and the stars was enough.

We talked about what had happened here. Who had died. Who had fallen ill. About hunting ptarmigans in the hills and about a neighbour’s bitch that had been successfully mated. The kind of things you talk about in villages like smalånger. We did not touch on why emelie had left him or why our childhood home was decaying.

For a second night I slept in a pullout bed. Too tired to undress, I used my coat as a blanket and fell asleep instantly.

In the morning I put on rubber gloves, filled a bucket with soapy water and systematically worked my way through room after room. That afternoon, there was a pile of rubbish bags on the steps. Bags full of beer cans pizza cartons dead potted plants newspapers food long past its best empty dog food cans bottles of spirits broken ornaments cracked picture frames and a whole lot of women’s clothes slashed to ribbons.

Everyone is good at something or so the saying goes. It pleased me to see the veined wood of the soapy boards and the glowing lime paint of the wooden cladding. It pleased me when boiling hot water dissolved grease vomit and other substances that had settled into a hard crust over tiling and workbench in fridges and the large larder. It even pleased me to see the washing spin as the machine sloshed months maybe years of dirt from sheets curtains mats clothes and in the end to hang all these things up in the drying cupboard. Cleaning was my way of dealing with my brother’s anguish as well as my own. A bit like playing tetris. The pieces fell into place and other thoughts I migh

t have attempted were kept at bay.

Bror sat on the kitchen sofa, eyeing me indifferently. He kept swigging bottled beer. When one bottle was empty he got another one from the larder. Maybe I was too late.

I heard you slept over at eskilbrännström’s he said.

You mean at john’s I countered hoping he would say more but he just shut his taciturn mouth tight and carried on staring out into the dangerous infinity.

I sat down next to him. Took the bottle from him and drank a mouthful of the tepid beer.

Do you know john I asked.

Sure everybody knows him bror replied.

I don’t I said.

He hasn’t been living there for all that long bror said.

Could be I said and then reconnected with reality. You have no food in the house. We must go shopping.

He leaned against me and if I hadn’t known my brother so well I might have thought he was crying.

He smelled badly of grief and sweat. I put my arm around him and stroked his hair as I had done in the past. It will be all right I said. It will be all right.

THREE

I reversed the jeep out of the garage and tied the rubbish bags onto the trailer. Bror was taking his time.

At last he opened the door to let the cat out. It looked around then slunk down to hide under the veranda.

After the cat bror came out with the hood of his jacket pulled down over his head. He looked around then slipped into the passenger seat. Pushed frantically at all the buttons to start the heater.

His skin was pale grey. Even his freckles had faded. His hair was unkempt and greasy. He pulled strands back behind his ears over and over again.

It was slippery after the snowfall and the car lurched a bit going downhill. At the side road to eskilbrännström’s I slowed down to a crawl to look for tracks in the snow. The private road was innocently smooth.

You know nothing about john said bror. He isn’t a bad man but you know nothing whatever about him.

No I don’t and he knows nothing about me I said. Well nothing except that I murdered my father but I guess everyone knows that.

My Brother

My Brother